Research Focus

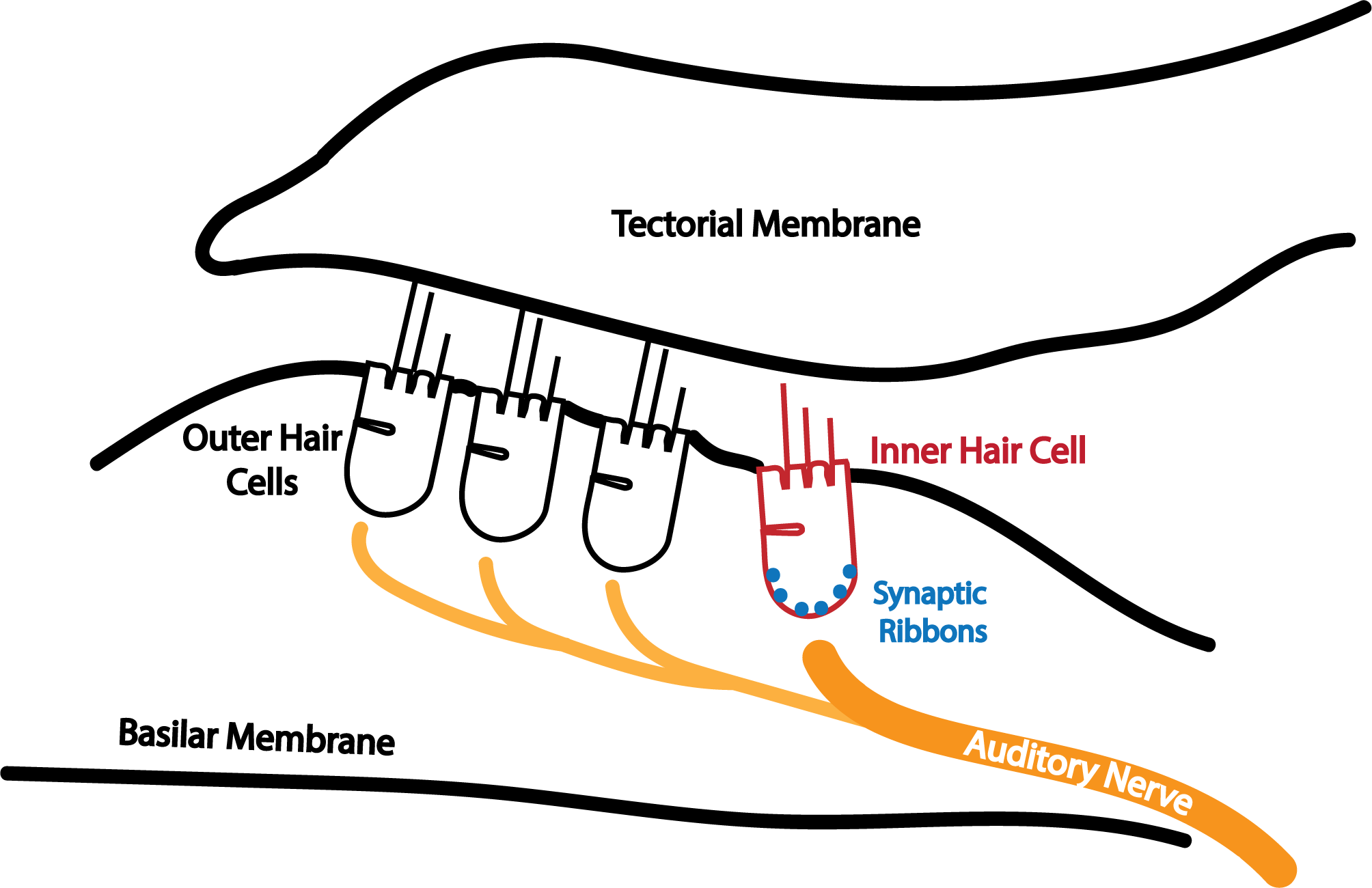

The cochlea is a snail-shaped organ in our inner ear that is our gateway to the marvelous world of sound. It is tonotopically organized, that is, higher frequency sounds are processed earlier in the cochlea, whe low frequency sounds are processed near the end of the cochlea. Several microscopic structures present in the cochlea are responsible for transforming variations in pressure into neural impulses. These impulses are rapidly conveyed by the auditory nerve to the brainstem, which transmits this sound information to the thalamus and cortex, where we can perceive or “listen” to our surroundings.

My work primarily involves studying how outer hair cells (OHCs), inner hair cells (IHCs), and the cochlear synapse work in harmony to capture these sounds. Specifically, I’m interested in the neural coding of pitch, the perceptual correlate of periodicity. In simple terms, good pitch perception helps us differentiate voices in a conversation or rank notes on a musical scale. Without pitch, a conversation lacks emotion, and a symphony becomes cacophony.

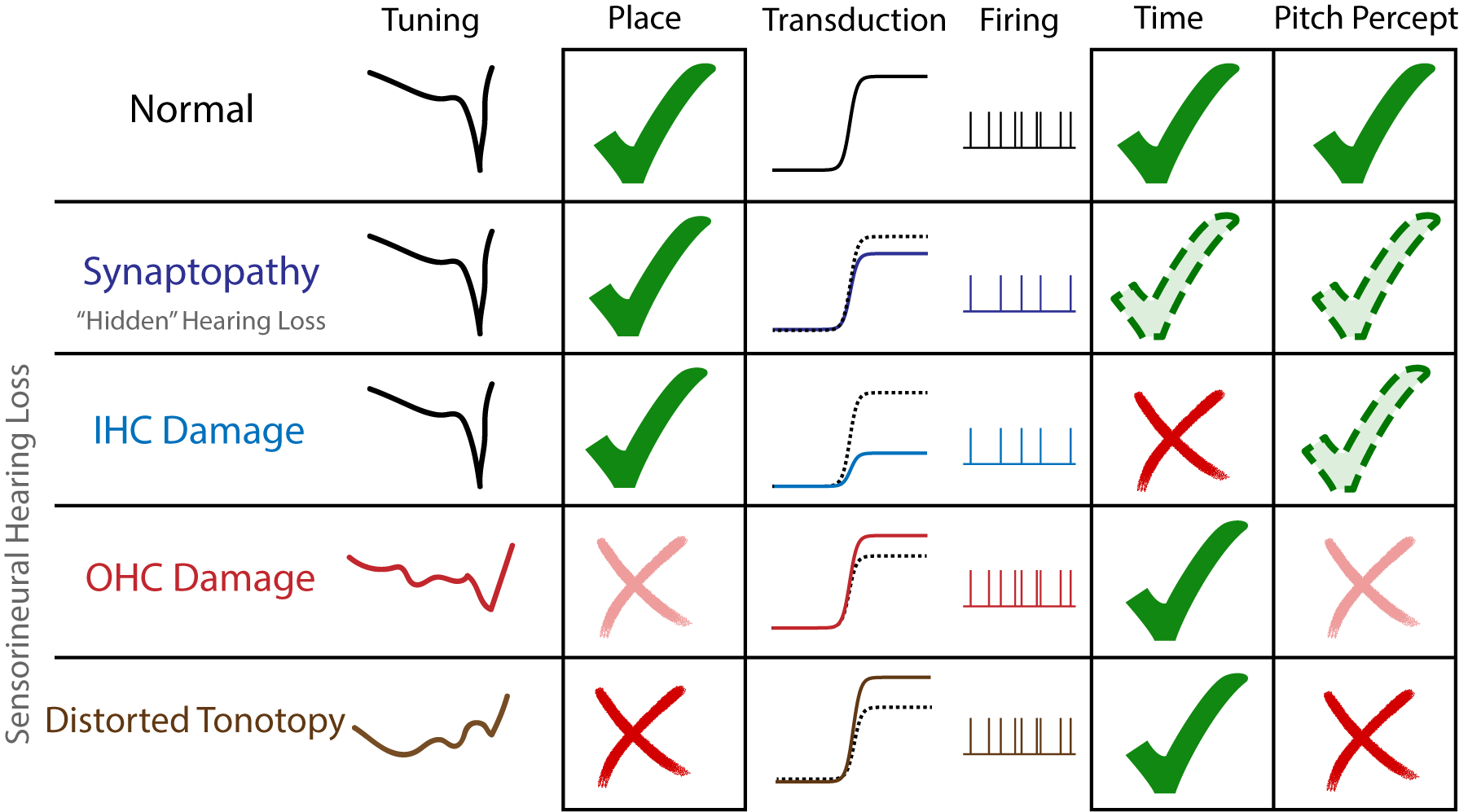

But what features of the cochlea lead to good pitch perception? Why do people with hearing loss tend to have worse pitch perception? These questions have been investigated and debated for centuries. Over these years, scientists have categorized pitch theories into those based primarily on timing cues, place cues, or a combination of the two. Timing cues depend on the precision of auditory nerve firing, while place cues depend on the tonotopic organization of the cochlea.

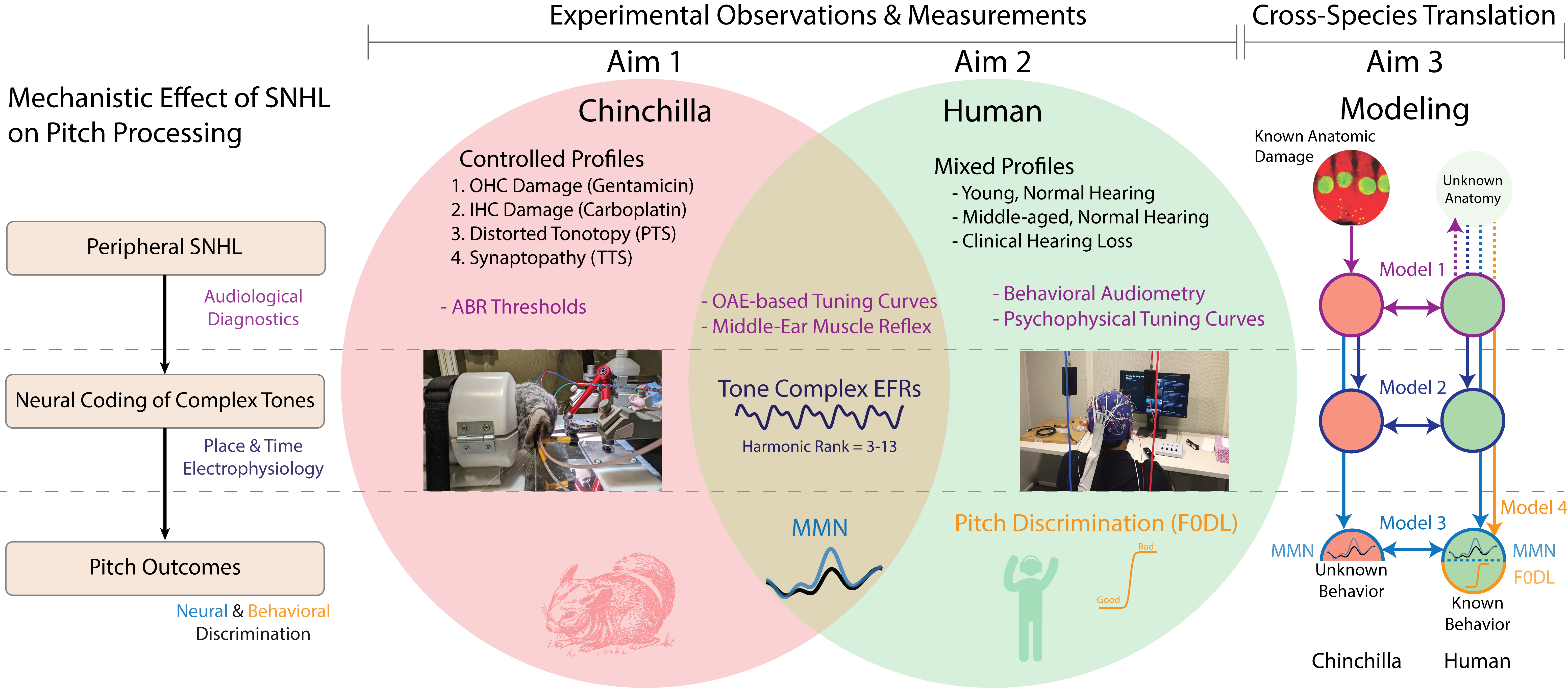

When it comes to hearing loss, previous scientific experiments from our lab (and others) imply that certain profiles or patterns of hearing damage differentially alter place vs timing cues. Profiles of damage that primarily affect OHCs more likely disrupt place, while those that disrupt IHCs and the cochlear synapse likely reduce timing. We can use these profiles to study the place vs time importance of pitch processing, while also understanding why pitch perception worsens with certain types of hearing loss.

Humans with clinically-diagnosed hearing loss likely have variations in OHC, IHC, and cochlear synapse damage, which we predict results in differences in pitch perception. Unfortunately, clinical diagnostics can not yet accurately profile the distribution of OHC, IHC, and cochlear synapse damage in a patient specific manner. However, animal models of hearing loss are relatively controlled, and we can use a combination of audiological diagnostics, electrophysiology, and predictive modeling in both humans and chinchillas to estimate what anatomic deficits most likely worsen pitch perception.

As we gain this insight, our work will help engineers, clinicians, and scientists develop better treatments and understanding of sensorineural hearing loss.

This work is currently supported by my NIDCD Ruth L. Kirschstein Predoctoral MD/PhD Fellowship

1F30DC020916

.